Antisense technologies are techniques that enable the study of gene function (functional genomics) and important research on animal and plant diseases. Via hybridization of antisense nucleic acid sequences with an RNA target, antisense technologies perturb normal cellular processing of a gene's genetic message through several different mechanisms [1].

Chemical evolution of antisense oligos (ASOs)

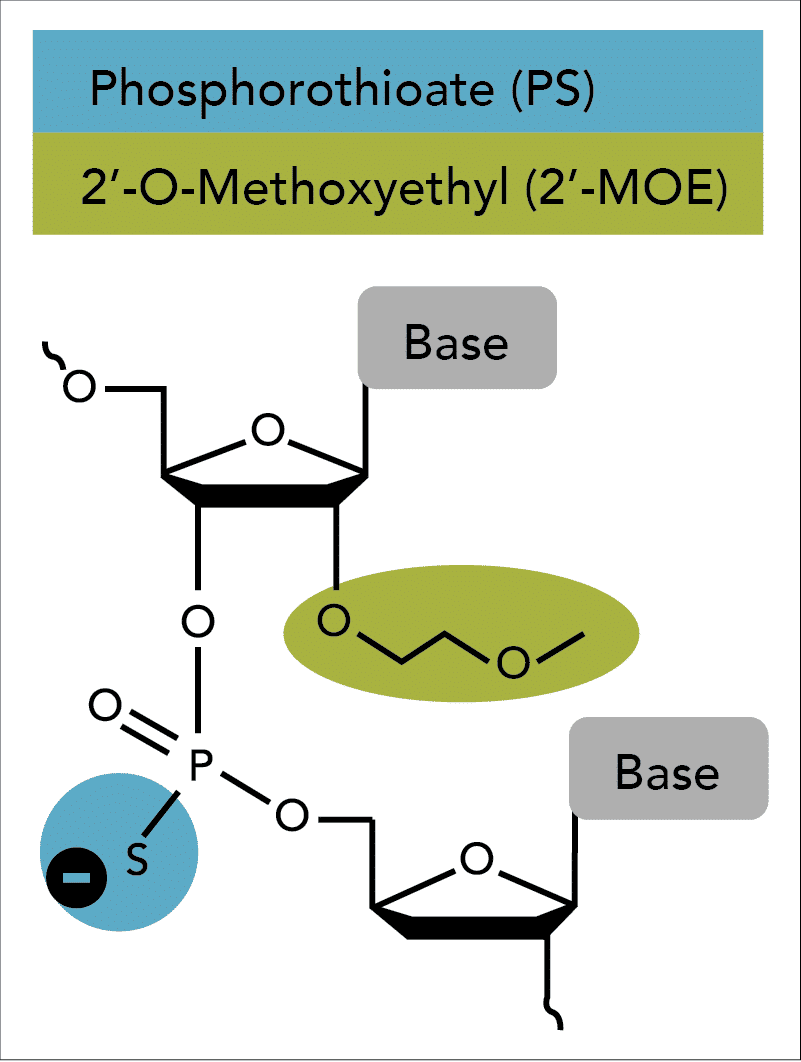

Oligonucleotide-based antisense techniques represent one of the most common and successful approaches to suppress a genetic message. ASOs require chemical modifications to be sufficiently active in vivo [2]. The first-generation antisense technique was introduced by Eckstein and colleagues in the late 1960s. This group replaced one of the non-bridging oxygen atoms in the phosphate backbone of an oligo with a sulfur atom [3,4]. While this “phosphorothioate modification” improved nuclease resistance in plasma, tissues, and cells, the phosphorothioated oligos displayed a tendency for non-specific binding with certain proteins that resulted in cytotoxicity when delivered at high concentrations [5,6].

Second generation antisense techniques address cytotoxic issues by introducing modifications at the 2′ position of the sugar moiety. Among these modifications, 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) has emerged as one of the most advanced analogs and provides the greatest value for enhancing the properties of oligonucleotides (Figure 1) [7–11]. ASOs containing 2′-MOE modifications display enhanced nuclease resistance in concert with lower cell toxicity and increased binding affinity to the desired target. Oligos containing 2′-MOE, in combination with other chemical modifications, have advanced a number of antisense drugs to clinical testing, which transitions antisense technologies from the test tube to actual disease treatment [12].

Use of 2′-MOE on RNase H-dependent ASOs

2′-MOE modifications are used broadly to support a variety of antisense mechanisms. One of the most common of these is RNase H cleavage. ASOs fully composed of sugar-modified RNA-like nucleotides (such as 2′-MOE), however, do not support RNase H cleavage of the complementary RNA. This limitation has been circumvented by constructing a hybrid oligonucleotide in the form of a “gapmer” (Figure 2). A standard gapmer retains a central region of PS-modified DNA bases sufficient to induce RNase H cleavage. These bases are flanked on both sides by blocks of 2' modifications that will increase binding affinity to the target. Once delivered to cells, ASOs enter the nucleus and bind to their complementary, endogenous RNA target. Hybridization of the ASO gapmers to target RNA forms a DNA:RNA heteroduplex in the central region, which becomes a substrate for cleavage by the enzyme RNase H1 [13].

While the use of such chimeric oligos enables RNase H-mediated degradation, it also provides a solution to another antisense issue. Non-specific cleavage can occur when portions of ASO sequences bind promiscuously within an RNA population. However, the shorter, targeted central sequences of gapmers, bound by the uncleavable RNA analogs, to a large extent, mitigate this problem.

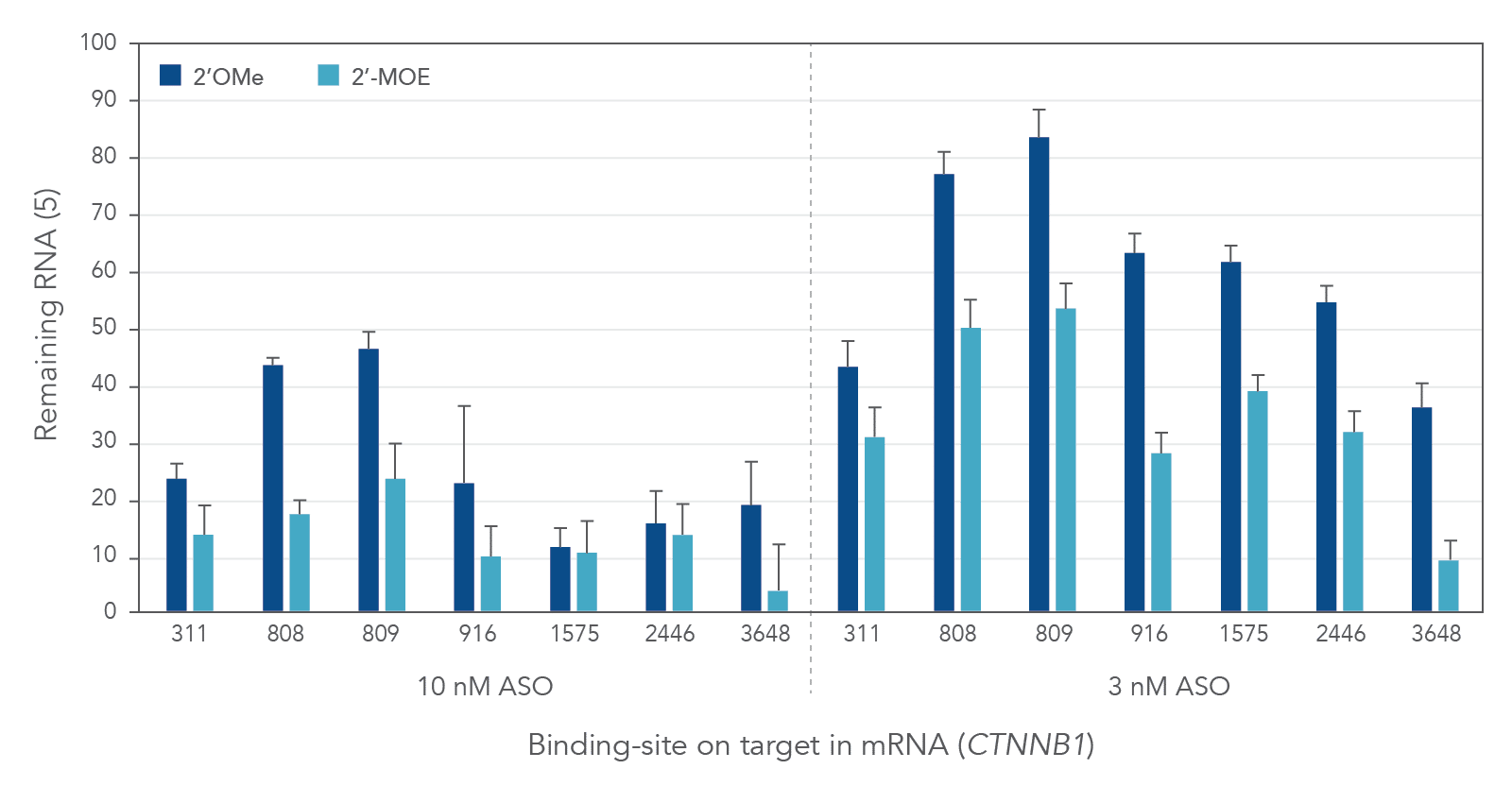

Compared to 2′-O-methyl (2′OMe)—another commercially available 2′ substitution, 2′-MOE gapmers provide more consistent knock down of endogenous gene expression. As shown in Figure 3, the potency of 2′OMe and 2′-MOE modified ASO gapmers was assessed and compared at the same 7 target sites in the human gene CTNNB1. As expected, 2′-MOE ASOs were consistently more effective at suppressing RNA levels than were the same sequences modified by 2′OMe.

Steric blocking ASOs

Unlike ASO gapmers that trigger target degradation, steric blocking ASOs bind to their target RNA and sterically deny other molecules access for base pairing to the RNA. Typically, steric blocking ASOs are fully modified at the 2′ sugar position so that RNase H is unable to degrade the target RNA. Not surprisingly, one of the most widely used 2′ alterations on steric blocking ASOs is 2′-MOE.

Modulating alternative splicing is an important application of steric blocking ASOs. By blocking the protein-RNA binding interactions between splicing machinery components and the pre-mRNA, steric blocking ASOs can be used to manipulate the splicing repertoire of a specific transcript. This is particularly valuable for researching diseases caused by mutations that lead to abnormal splicing.

ASOs—past, present, and future

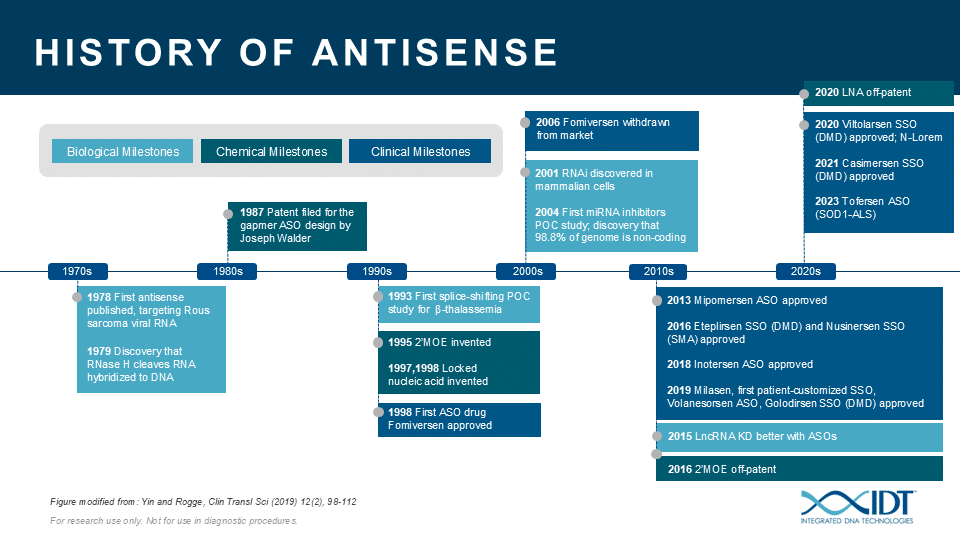

The potential for ASOs is just beginning to be realized. ASOs can be a valuable tool for studying the biological function of genomic elements or discerning genetic contributions to disease. During the past 30 years, IDT has been providing nucleic acid products and other innovative tools to drive research advances that inspire scientists worldwide to achieve milestones in antisense science (Figure 4)[13–23].

The 2'-MOE modification complements the IDT ASO product portfolio, containing PS and 2'-OMe bases. 2'-MOE modified bases are available at a broad range of scales.

Visit the ASO product page to find out more, or contact us with any questions about ordering modified ASOs, or to discuss your experimental design.

References

- Bennett CF, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol.

2010;50:259-293. - Khvorova A, Watts JK. The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(3):238-248.

- Eckstein F. Nucleoside phosphorothioates. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92(15):4718-4723.

- Eckstein F. Phosphorothioates, essential components of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2014;24(6):374-387.

- Gura T. Antisense has growing pains. Science. 1995;270(5236):575-577.

- Krieg AM, Stein CA. Phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides: antisense or anti-protein? Antisense Res Dev. 1995;5(4):241.

- Manoharan M. 2'-carbohydrate modifications in antisense oligonucleotide therapy: importance of conformation, configuration and conjugation. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1999;1489(1):117-130. - Freier SM, Altmann KH. The ups and downs of nucleic acid duplex stability: structure-stability studies on chemically-modified DNA:RNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res.

1997;25(22):4429-4443. - Mangos MM, Damha MJ. Flexible and frozen sugar-modified nucleic acids--modulation of biological activity through furanose ring dynamics in the antisense strand.

Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(10):1147-1171. - Prakash TP. An overview of sugar-modified oligonucleotides for antisense therapeutics. Chem Biodivers. 2011;8(9):1616-1641.

- Egli M, Minasov G, Tereshko V, et al. Probing the influence of stereoelectronic effects on the biophysical properties of oligonucleotides: comprehensive analysis of the RNA affinity, nuclease resistance, and crystal structure of ten 2'-O-ribonucleic acid modifications.

Biochemistry. 2005;44(25):9045-9057. - Bennett CF, Baker BF, Pham N, et al. Pharmacology of Antisense Drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:81-105.

- Walder RY, Walder JA. Role of RNase H in hybrid-arrested translation by antisense oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(14):5011-5015.

- Dagle JM, Weeks DL, Walder JA. Pathways of degradation and mechanism of action of antisense oligonucleotides in Xenopus laevis embryos. Antisense Res Dev.

1991;1(1):11-20. - Dagle JM, Walder JA, Weeks DL. Targeted degradation of mRNA in Xenopus oocytes and embryos directed by modified oligonucleotides: studies of An2 and cyclin in embryogenesis.

Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(16):4751-4757. - Eder PS, DeVine RJ, Dagle JM, et al. Substrate specificity and kinetics of degradation of antisense oligonucleotides by a 3' exonuclease in plasma.

Antisense Res Dev. 1991;1(2):141-151. - Conrad AH, Behlke MA, Jaffredo T, et al. Optimal lipofection reagent varies with the molecular modifications of the DNA. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev.

1998;8(5):427-434. - McQuisten KA, Peek AS. Identification of sequence motifs significantly associated with antisense activity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:184.

- Pauli A, Montague TG, Lennox KA, et al. Antisense Oligonucleotide-Mediated Transcript Knockdown in Zebrafish. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139504.

- Lennox KA, Behlke MA. Cellular localization of long non-coding RNAs affects silencing by RNAi more than by antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res.

2016;44(2):863-877. - Ezzat K, Aoki Y, Koo T, et al. Self-Assembly into Nanoparticles Is Essential for Receptor Mediated Uptake of Therapeutic Antisense Oligonucleotides.

Nano Lett. 2015;15(7):4364-4373. - Hammond SM, McClorey G, Nordin JZ, et al. Correlating In Vitro Splice Switching Activity With Systemic In Vivo Delivery Using Novel ZEN-modified Oligonucleotides.

Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2014;3:e212. - Rocha CS, Lundin KE, Behlke MA, et al. Four Novel Splice-Switch Reporter Cell Lines: Distinct Impact of Oligonucleotide Chemistry and Delivery Vector on Biological Activity.

Nucleic Acid Ther. 2016;26(6):381-391.1

RUO22-1581_001